A Durban International Film Festival Film - Karl Marx City has messages for South Africa and the world.

By Wanda Hennig

German-born New York film-maker Petra Epperlein was at home in the United States with her co-director husband Michael Tucker when she received the devastating news. Her father was dead. He had hanged himself from an oak tree in the garden of the family home. The home her mom still lived in. The home that for the first 20 years of Epperlein’s life (and for 20 years before that) was in Soviet-controlled East German, the old German Democratic Republic (DDR).

There had been no warning signs that her dad was planning to end his life.

What Epperlein did know, however, was that after the Berllin Wall fell in 1989 and as the process of reunification was beginning, he had been mailed several veiled threats. Notes accusing him of having been in alliance with the sinister, controlling Stasi, the Ministry of State Security “secret police” that had created a society under constant “Big Brother” surveillance and in the grip of fear: even of thinking the wrong thoughts.

So was born the intimate and personal documentary Karl Marx City, the film that has brought Epperlein to the 2017 Durban International Film Festival. It is one of 10 “German Film Focus” films screening: a collaboration between the German Embassy, the Goethe-Institut, German Films and Berlinale Talents, with DIFF 2017. Epperlein, also part of DIFF’s women-led films focus, will share knowledge with aspiring film-makers while here.

Karl Marx City was the city of Chemnitz before the 40-year DDR period. With the name change came a 40-ton bronze monument of Marx’s head that still looms over the inner city skyline: even though the city is Chemnitz once more.

“My father’s suicide made me question my memories of him. Do we really know who our parents are? You live with them. You see them in a certain way. I had a perception of my father as a warm and loving person.”

But with his suicide she began to question her memories. Could her childhood have been an elaborate fiction? Could her father in fact have been an informant? The Stasi were known to have had neighbour spy on neighbour; children report on parents.

We are chatting at the Elangeni Hotel. Epperlein is just off the plane from New York City. The gaminesque architect turned film-maker is shiny-eyed from jet-lag but alert, curious about Durban (“what mustn’t I miss?) and happy to share both perceptions on her movie and the fact that Karl Marx City—the fourth film she and Tucker have made to premier at the Toronto Film Festival—has received fantastic reviews in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times and elsewhere.

Epperlein was an architecture student at university in Dresden when the Berlin Wall fell. The revolution that saw the Cold War unravel started in Dresden. She was in the thick of it. Scenes from the time feature in her film. East Germans were trying to escape to the West in growing numbers. Many had sought refuge in embassies in Budapest and Prague. The DDR regime agreed to give passage to the unsustainably large numbers holed up there. They would be taken by train to (west) Berlin. The train would pass through Dresden. The aim was for Stasi officers to board the train in Dresden and take away passports “so they could never return”.

But riots erupted. You see footage of the riots is in the film. “It was the first riot against the regime. I was there and it was four weeks of true excitement.”

Within a month the wall came down.

Two years later, soon as she completed her degree, Epperlein moved to Berlin. “The city centre didn’t exist. It was unchartered territory,” she says. “There were clubs and parties and excitement. Young people moved in and claimed it as their own—until the capital came in and started claiming it.”

After two years in Berlin, where she worked as an architect, Epperlein booked a ticket to New York City. “The ultimate symbol of freedom. I went to check it out.” She found it lived up to its promises and cliches.

It gave her something else too. She met Michael Tucker, the guy who became her husband. He was a film-maker. They became not only partners but also film collaborators. “Film-making and architecture are pretty similar,” she says. “With both, you have to organize complex structures in time and place.”

Epperlein’s father suicide came shortly before the 2013 Edward Snowden National Security Agency (NSA) leaks in the US. “Inspiration for the film came via the NSA leaks. People started comparing the Stasi to the NSA. This bothered me. They were really not the same. The Stasi were a repressive communist regime. You were not permitted to express your view or dissent. The NSA operates within a democratic society.

“I realised how little people knew about the Stasi or what life was like behind the Iron Curtain. East Germans don’t want to talk about it 27 years after reunification. It hasn’t been processed. Questions, for example about complicity, haven’t been addressed. It’s complex. So many questions.

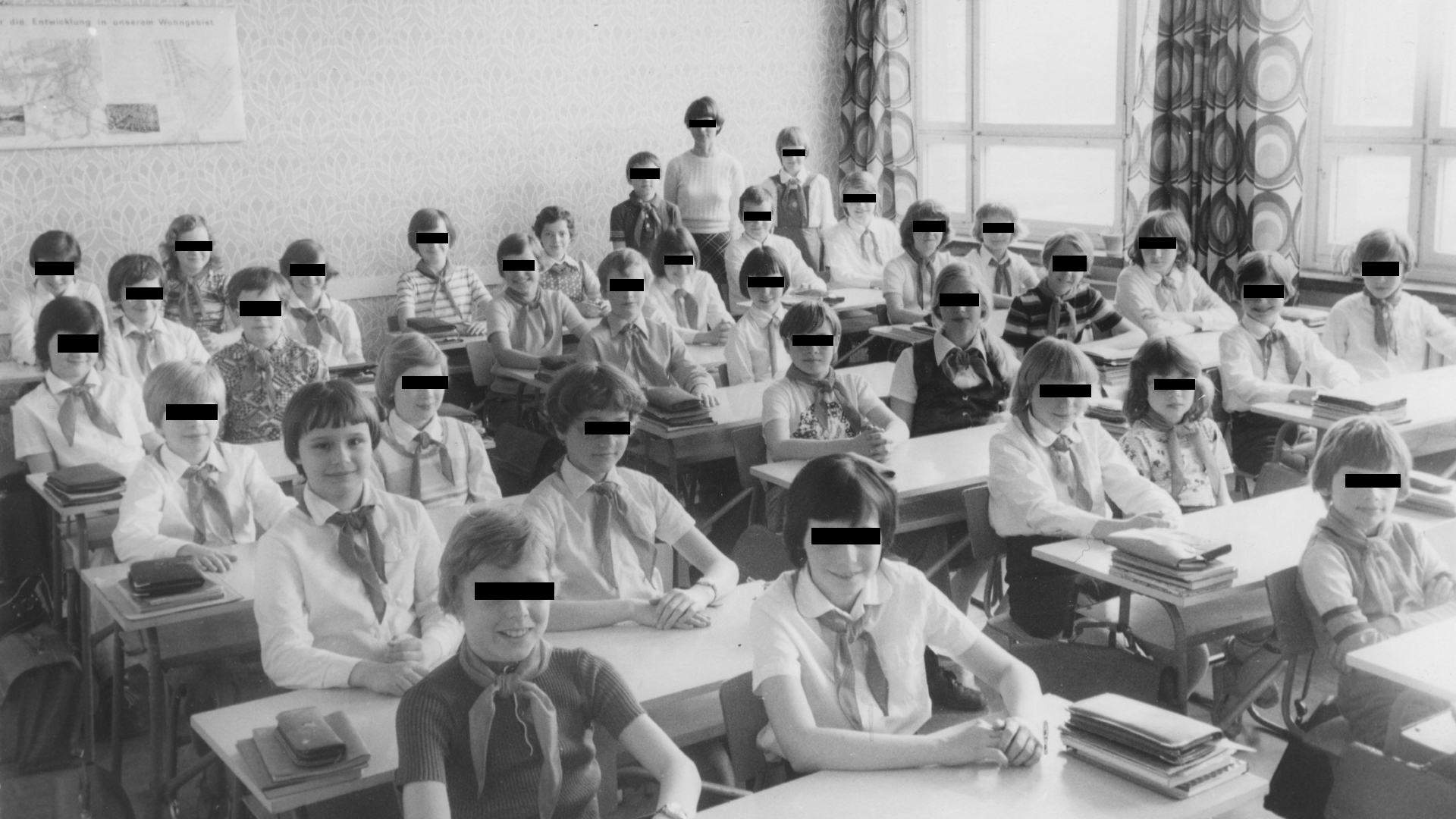

“I thought, before it slips away and is lost, we should make a film about it. The final decision came after we went to the Stasi archives and discovered the film and video archives. Endless hours of surveillance. Mind-blowing. So much of it banal. The banality of evil. Unsuspecting people unaware they were being watched. Almost perfect documentary material.”

At the start of their quest, to try and find answers via the Stasi files, Epperlein had to convice her mom and her twin brothers that addressing this via a doccie was a good idea. “It was my obsession, to try and find the truth about my father. I imposed it on them. They were at first opposed. But then they went along.” The experience, she says, has brought them closer.

This is a film that will resonate with many South Africans who lived through apartheid. Think Broederbond and the Bureau for State Security (BOSS). Even the recent revelations of the Bell Pottinger secret manipulations... On a more intimate level, the family relationships resonate.

Epperlein and Tucker sponsor their own movies. They make them, then set about selling them. One called Fightville about cage fighting—“some amateur fighters who think their way of fulfilling the American dream is to go into a cage and beat each other up”—made them a bunch of money a couple of years ago.

It supported the current film “about a world that doesn’t exist any more.” Yet has profound lessons in the world we live in now where constant surveillance is a given. “It’s good to be aware of what it feels like to live in a truly oppressive society.”

The Stasi, she laughs, would have loved Facebook.

Karl Marx City shows tonight ( July 17) at 5pm (one screening only) at Gateway Sterkinekor during the Durban International Film Festival which runs until Sunday, July 23. Tickets for this screening at box-office or www.sterkinekor.com. For more information about the DIFF go to www.durbanfilmfest.co.za.

-ends